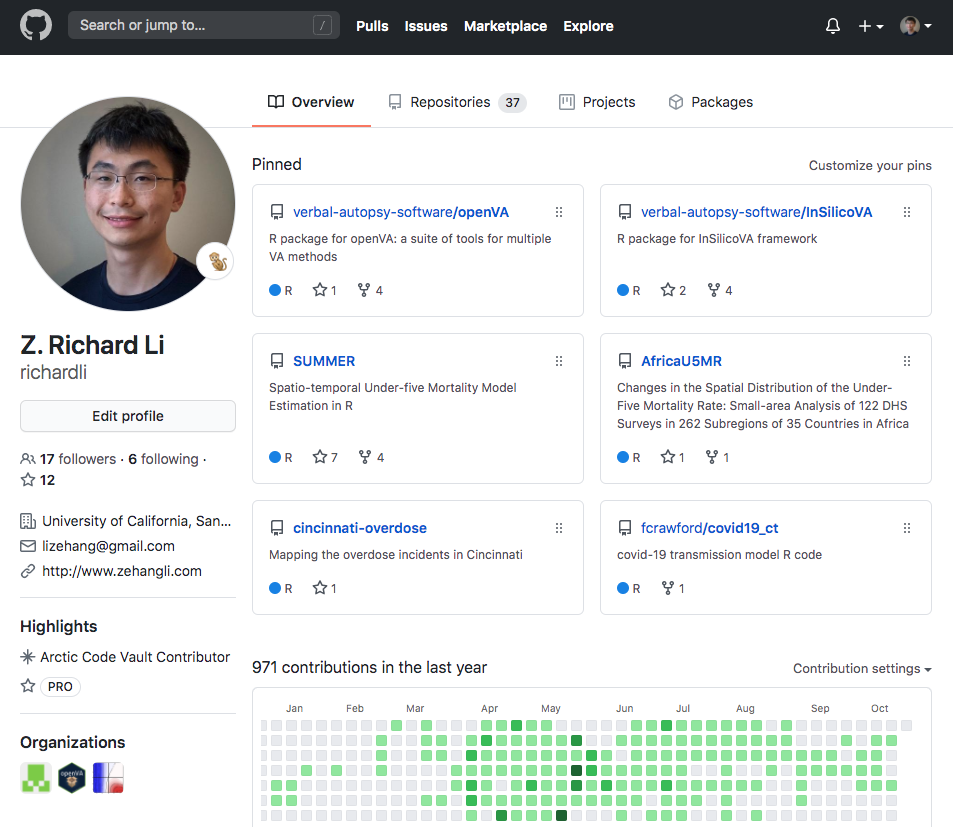

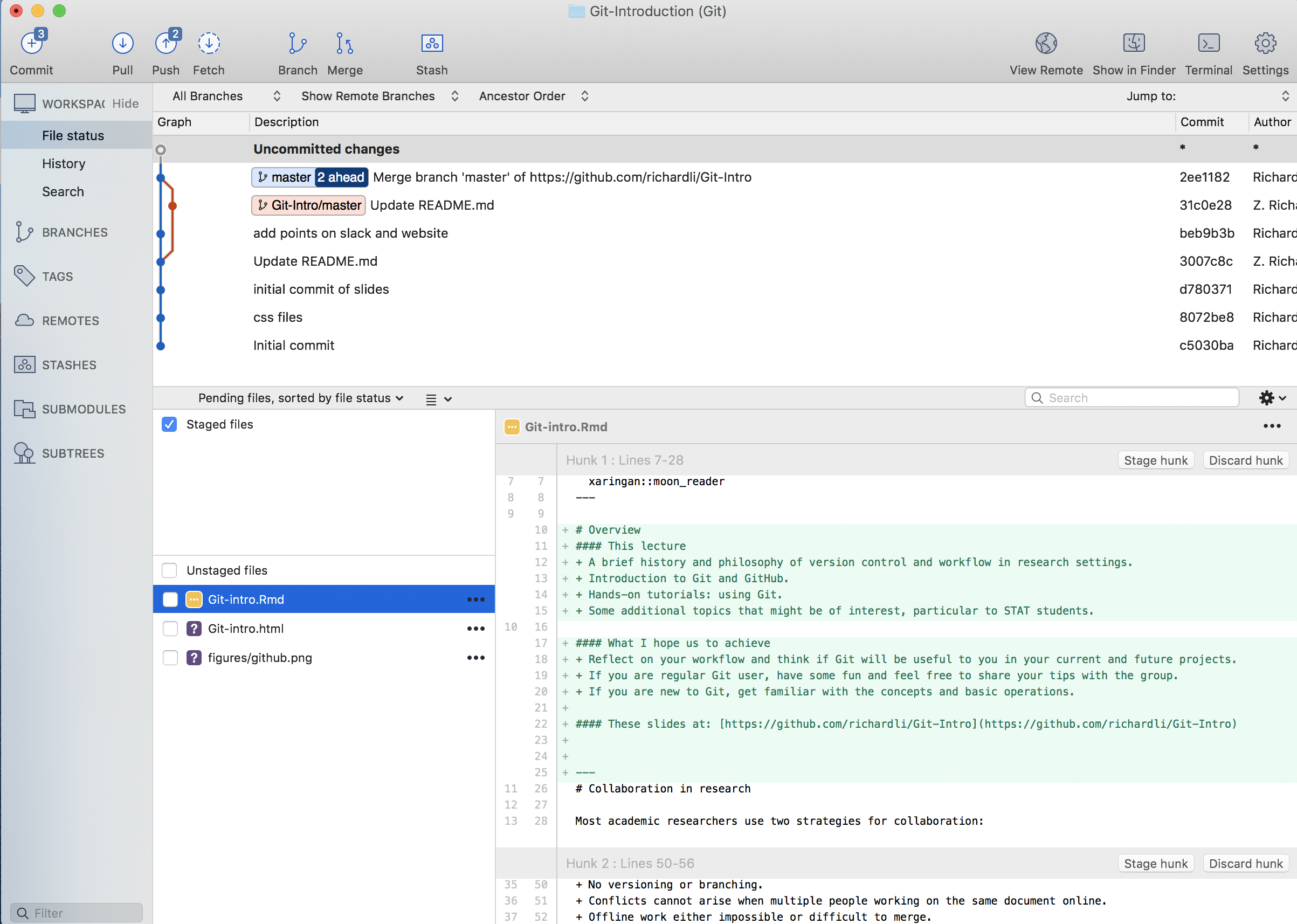

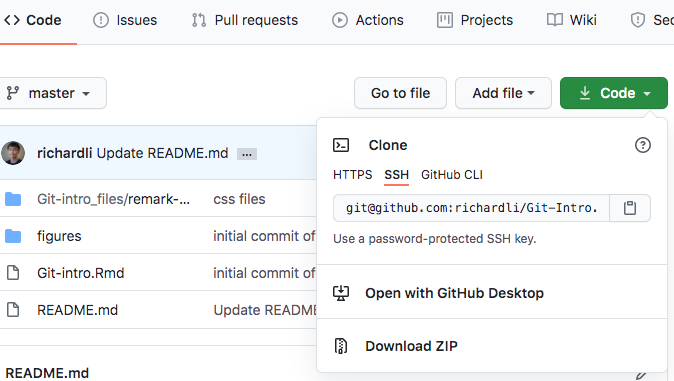

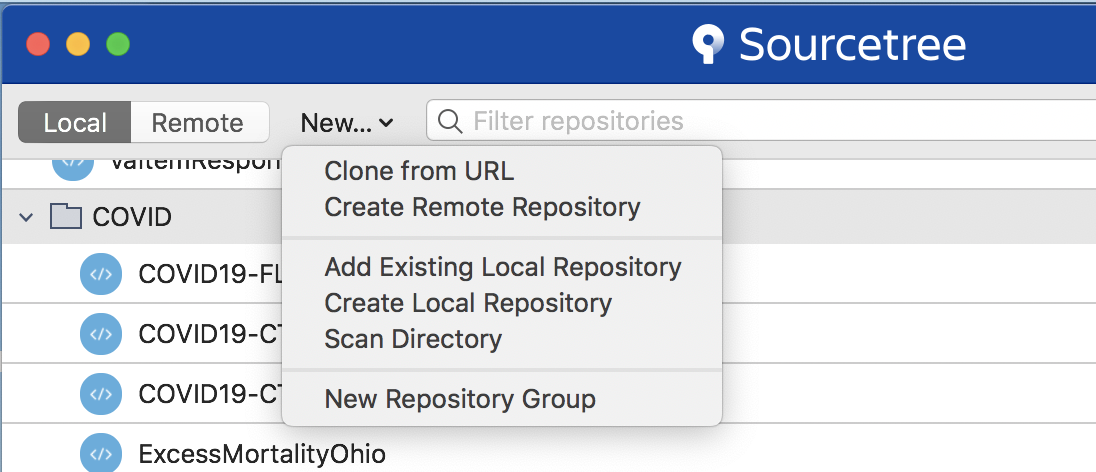

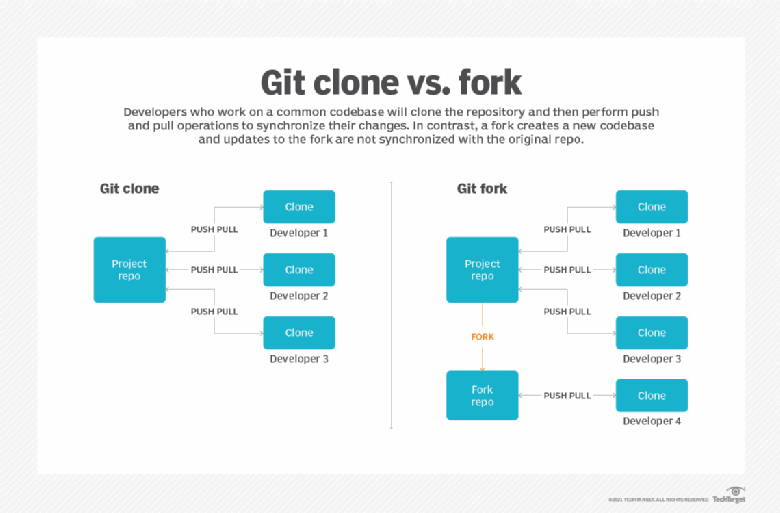

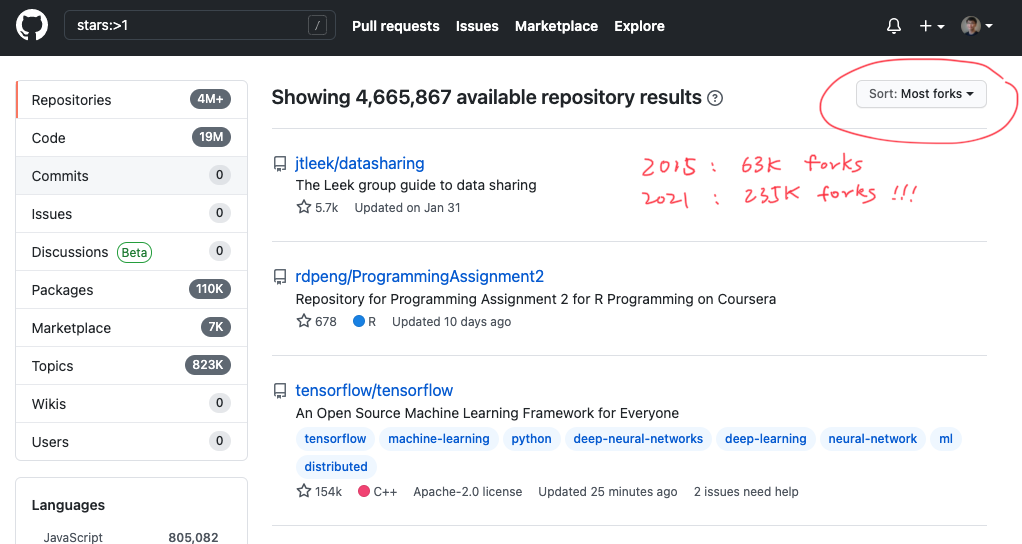

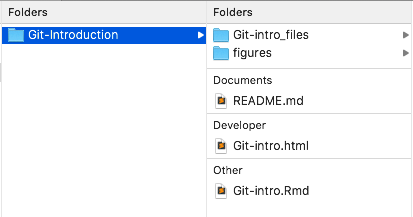

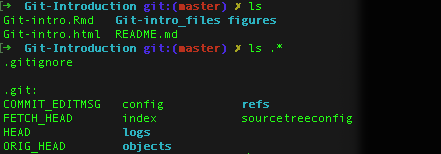

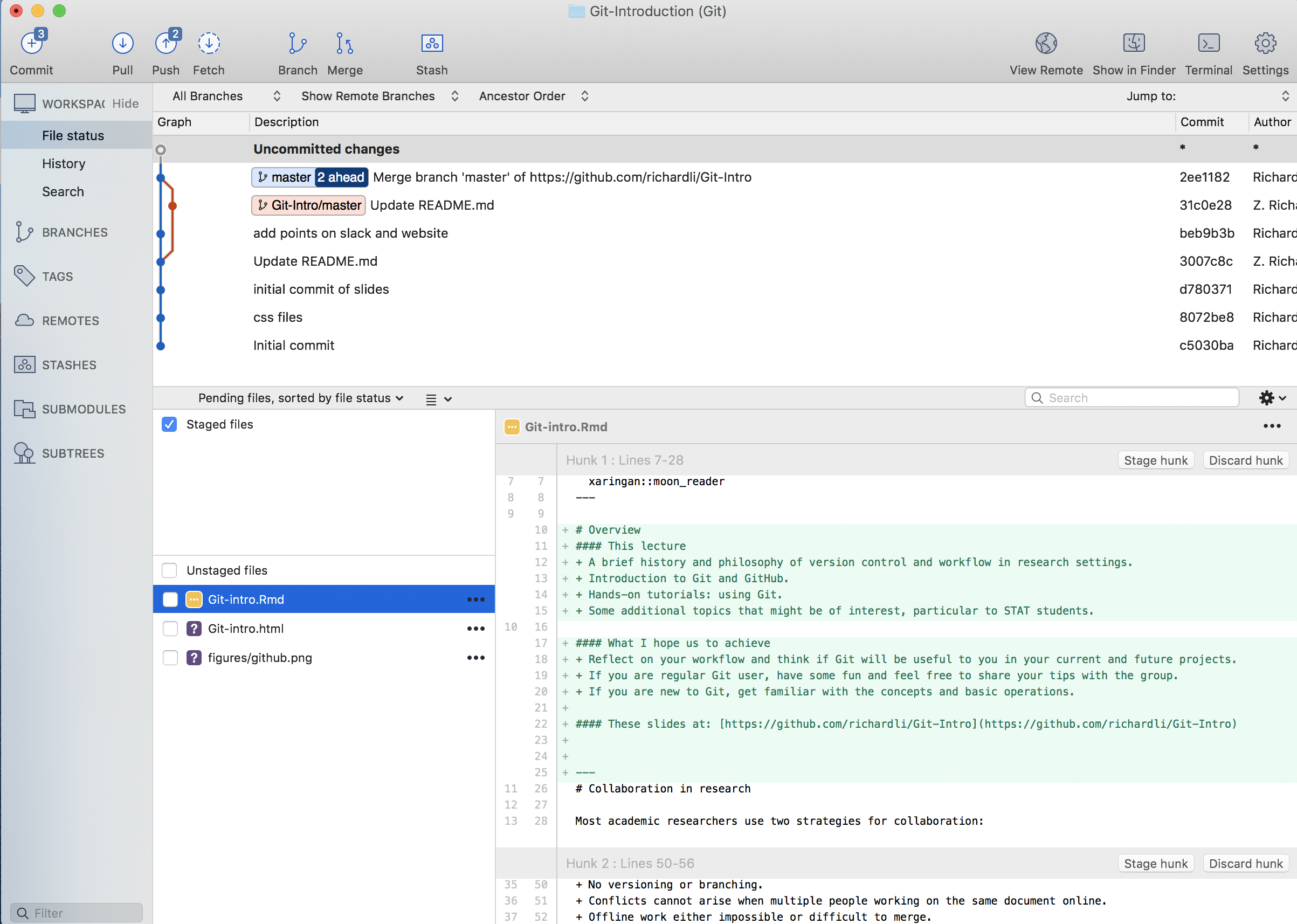

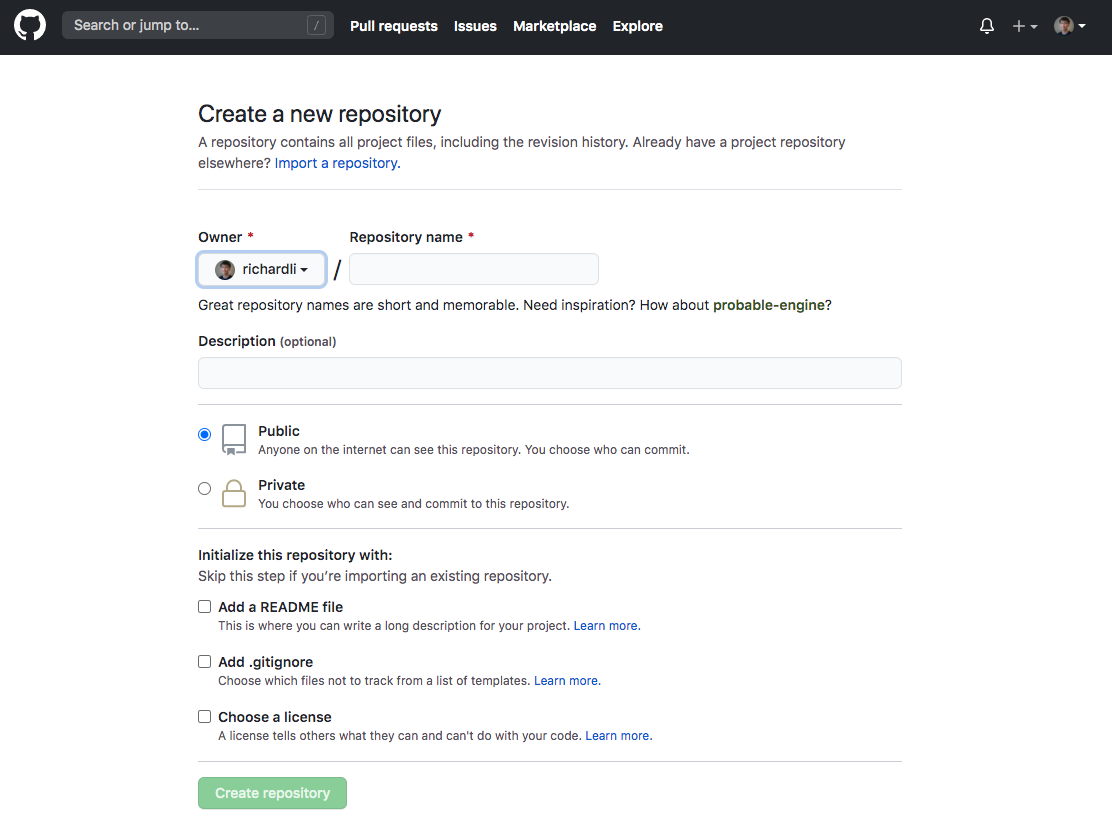

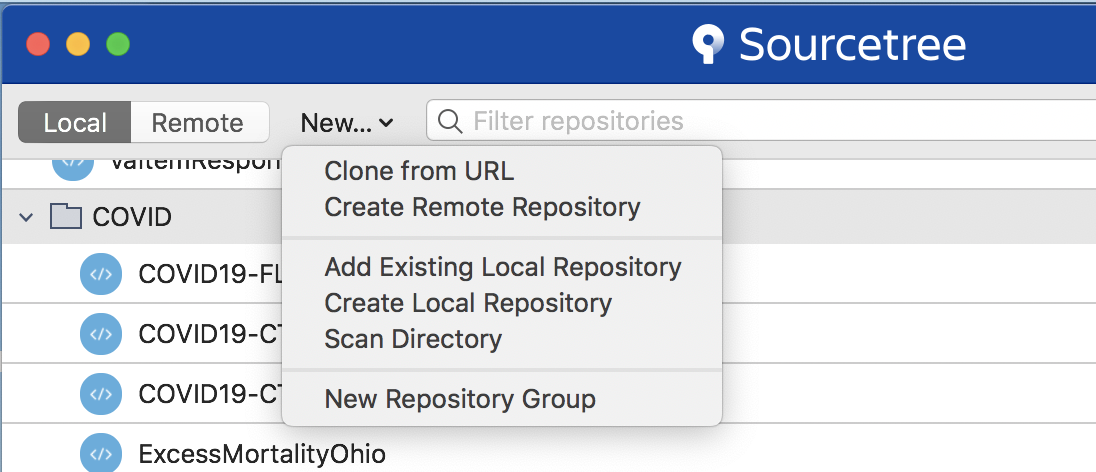

class: center, middle, inverse, title-slide .title[ # Git and GitHub for Collaboration ] .author[ ### Z Richard Li ] .date[ ### Fall 2023 ] --- # This lecture -- + A brief history and philosophy of version control and workflow in research settings. -- + Introduction to Git and GitHub. -- + ~~Hands-on tutorials: using Git.~~ -- + Some additional topics that might be of interest, particular to STAT students. -- #### What I hope us to achieve + Reflect on your workflow and think if Git will be useful to you in your current and future projects. -- + If you are regular Git user, have some fun and feel free to share your tips with the group. -- + If you are new to Git, get familiar with the concepts and basic operations. #### These slides at: [https://github.com/richardli/Git-Intro](https://github.com/richardli/Git-Intro) --- # Collaboration in research Most academic researchers use two strategies for collaboration: **Shared Folders (Dropbox/Box/Google Drive)** -- + Single synced shared folder. + `draft_20190717.tex` + `draft_20190719_old_backup.tex` + `submit_final_final_v3.tex` + Simultaneous editing results in conflicts. + `submit_final_final_v3 (MIKE D's conflicted copy).tex` + Restoring older version is possible. + Offline work is possible. + Resolving conflicts of different versions manually. --- # Collaboration in research **Online concurrent editing (Google Docs/Overleaf)** -- + Single synced shared file. + Simultaneously editing. + Previous versions stored online. + No versioning or branching. + Conflicts cannot arise when multiple people working on the same document online. + Offline work either impossible or difficult to merge. + Difficult (impossible?) for collaborative coding projects. --- # Problems These strategies work well for rich text document when there is a single main version. -- Managing complex projects can be difficult when you have + many files, directories, and dependencies, + many people contributing and making edits on different files, + different "working versions" that are similar and exist in parallel for a period of time. -- These approaches do not scale to complex collaborative projects. Someone needs to be on top of all the files and changes to fix any errors (without destroying other changes). -- In software engineering, workers have developed _social and technological solutions_ to the problem of managing collaborative work. The technological aspect of this system is usually called _version control_. --- # Why version control Version control helps team (or even individual!) manage and keep track of changes over time. In collaborative work, it is not reasonable to block collaborators from working on the project while one person makes changes to a single file It is easier for team members to work in parallel and keep track of each change: who made what change at what point in time and why. Merging multiple changes on the same file is always painstaking -- what if there is a tool to make it somewhat automatic and easier to track? --- # Git Git was created by Linus Torvalds, the inventor of Linux, in 2005 to manage work by hundreds of developers on the Linux kernel. Git was designed for software development by large teams. But it is useful for many kinds of projects. -- **Big ideas** + distributed, parallel workflow + every contributor has a full copy of the repository and its history + fast and scalable. --- # Git Unfortunately Git can be difficult to learn for people unfamiliar with modern software development practices and newcomers to version control. <img src="figures/git-doc-example.png" width="50%" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> --- # GitHub GitHub is an online platform for hosting Git repositories. GitHub offers many additional services: + Access control + Issue tracking + Pull requests with code review and comments + Markdown rendering + Gists + Wikis + GitHub pages + Integration with other productivity/teamwork apps (e.g., Slack) An academic GitHub account with unlimited public and private repositories is free. --- .center[] --- # Getting started with Git Do you have Git? On the UNIX command line (terminal app in mac and cmd in windows), type: ```bash git --version ``` If you do not have Git, follow these instructions: [https://www.atlassian.com/git/tutorials/install-git](https://www.atlassian.com/git/tutorials/install-git) If you do not have an GitHub account, sign up at: [https://github.com/](https://github.com/) --- # Graphical interfaces to Git GitHub Desktop and Sourcetree are two of the most popular GUIs. I will use Sourcetree in this tutorial. You can connect your GitHub account (or other online platforms) to Sourcetree in `Preferences > Accounts`. .center[] --- # Password & sign into GitHub + Unfortunately as of right now, this process is not as straightforward as it sounds... -- + Since August 2021, GitHub has removed the password as a method of authentication if you would like to push from a software client. -- + Instead what you need is a **personal access token**, which is essentially a complex password GitHub generates for you and show you only once... -- + So here is how it works: -- + On Github.com, generate a personal access token via: Settings → Developer Settings → Personal Access Token → Generate New Token. Copy the new token (again, this is the last time you will see it). -- + On Sourcetree, go to Settings → Accounts. Select GitHub as Host, Basic as Auth Type, and use your token instead of password as "Password". -- + When you perform your first push to Github, a pop-up window will appear to ask if you allow the use of the token (and you need to approve with your computer password). Choose "Always allow" if you are on your own personal computer. Otherwise it will appear every time for authentication. -- + GitHub is also moving towards two-factor authentication for signing in on the web too (happening now). --- # Basics of Git workflow Today I will cover only a small part of the workflow: 1. Clone a remote repo 2. Create your own local or remote repo 3. Making and tracking changes 4. Merging changes from someone else These simple steps cover a large proportion of routine workflow with Git. --- # Tutorial I: clone to your computer .center[[https://github.com/richardli/Git-Intro](https://github.com/richardli/Git-Intro)] .pull-left[ From the web page:  ] .pull-right[ From Sourcetree:  ] These are your local copies. Making local changes does not affect the upstream repo (in my account). You will not have an online "copy" of the repository. What if you want to collaborate in someone else's repo? + Ask to be added as collaborator + Fork and Pull request (propose one-time changes to others' repos) --- # clone v.s. fork  --- # Fun fact: most forked repository of all time on GitHub .center[] --- # Tutorial I: look inside a repo .pull-left[  ] .pull-right[  ] + **README** + Things the authors want people to know upfront. + **.git** + A directory of lots of goodies in your project -- you don't need to interact with it directly. + **.gitignore** + A file that tells git which files should not be tracked. --- # Tutorial I: look into the past .center[] --- # Tutorial II: Create your remote repo .center[] --- # Tutorial II: Create your local repo .center[] --- # Tutorial III: More than Cmd+S In Git, a 'commit' is a collection of changes in the repository. #### Making changes + Edit the files #### Stage changes + The files that are ready to form the next *commit* #### Commit changes + Save the staged changes to the local repository and add message to yourself and others #### Push changes (if you have a remote repo) + Send the changes to the remote repo --- # Tutorial III: ~~Oops, scratch that~~ #### Checkout + Temporarily switching to a past point (remember not making changes) #### Revert + Undo the last commit #### Reset + Rest every _tracked_ file to a specific point in time (remember to check files in .gitignore) --- # Now, collaborating with Git Just using Git on your own is complicated. Using Git to collaborate with several other people on a project can be difficult. <img src="figures/xkcd.png" width="38%" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> <center> https://imgs.xkcd.com/comics/git.png </center> --- # Tutorial IV: Am I ready to push? + **Pull** before push * get the remote updates others have made. -- + If nothing shows up after pulling --> awesome! -- + Otherwise, likely you have a merge conflict * This happens when you and your collaborator made changes on the same lines of codes in the same file, that Git does not know how to resolve automatically. * You will need to tell Git what final version would be. * There are different tools to make the side-by-side comparison easier visually. * If you are in doubt, don't force it. Communicate with your collaborator. --- # Tutorial V: ~~Polluting~~ Improving other people's repository + There is another useful tool in Git that allows you to make suggestions to other people's codes. It is called **pull request** -- + The idea is that you work on a copy of the repository, make changes, and request the changes to be merged to the target branch (usually the main branch) of a repository. -- + The copy of the repository you work on can be a branch of the repository (if you have access to the repository itself), or a fork of the target repository (if you do not have access to it). -- + In general, it is useful to create branches in your repository if you need to set aside a team member (or yourself) to work on a specific portion of your codes, and use PR to communicate (or talk to yourself) before merging the branch back to main. --- # Pull request example <img src="figures/pr.png" width="70%" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> --- # Pull request example <img src="figures/pr2.png" width="50%" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> --- # Github issues page + This can be a very useful way to interact with code owners, e.g., if you run into a package error or have suggestions on package features <img src="figures/issues.png" width="80%" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> --- # Some practical considerations ###Some useful practices + Make small and frequent commits with detailed (and searchable) messages. + Git diff are line-based, so make lines small. + Break up codes into several files. + Try not to leave uncommitted changes open for a long time. + Use .gitignore wisely. -- ###Be aware of + Rich texts (e.g., .docx, .xlsx) + Very large files (e.g., high resolution pdf, large .RData files) + **Sensitive information (e.g., passwords, sensitive data)** --- # Additional topics ### Latex + `.gitignore` can be very helpful in maintaining only the necessary files to compile (no .aux, .log, .out, .bbl, .blg, ..., or even the paper.pdf) + Some people use a Makefile to compile, which can be useful when you have multiple .tex files. + Line break after each sentence is good for git diff to track, but can be annoying to collaborators (or yourself!) + Overleaf/ShareLaTex is a good alternative (when you have good internet). --- # Additional topics ### R packages + The GitHub repo is the package. + There are tools to make it easy to make releases, generate help files, and for others to install directly from GitHub and provide feedback. + Many more flexible features to write documents, vignettes, and websites, e.g., [pkgdown](https://pkgdown.r-lib.org/) + Tools to check your package can build, install, and 'works', e.g., [TravisCI](https://docs.travis-ci.com/user/languages/r) ### GitHub pages + A very useful way to set up your personal/professional website or specific projects: [pages.github](https://pages.github.com/). --- # So, will my Git now go smoothly? .center[] --- # Don't be discouraged! .center[### Git is expressly designed to make you feel less intelligent than you thought you were.] .right[-- Andrew Morton, when introducing Linus Torvalds <br>at a 2007 Google tech talk] <br> .center[### So I think it used to be true but isn’t any more. There is a few reasons people feel that way, but I think only one of them remains. The one that remains is fairly simple: “you can do things so many ways.” ... Generally, the best way to learn git is probably to first only do very basic things and not even look at some of the things you can do until you are familiar and confident about the basics.] .right[-- Linus Torvalds, 2015] # .center[ ## Git is like grad school, intimidating, mysterious, loads of written and unwritten rules, full of different opinions from everyone about everything... ### _but only a few trials and errors away from an organized and happy life :)_ ] --- # Resources There are many git tutorials out there. What if I have a problem? Google it. Likely you will find different people asking the same question over and over again over many years!